By Zoe Bowman, Supervising Attorney at Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center and Maria Archuleta, Communications Director at ACLU-NM

Editor's note: This is the second in a series of stories from inside the Otero County Processing Center, based on interviews conducted in the summer of 2024 by Colorado College students: Alex Reynolds, Sandra Torres, Karen Henriquez Fajardo, and Michelle Ortiz. We are grateful for their invaluable work on this project.

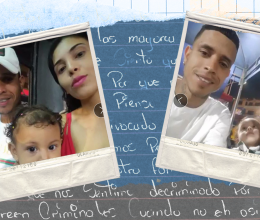

Yofer Fernando Orozco-Herrera, a basketball enthusiast from Barinas, Venezuela, dreamed of a career in public service. Instead, he was forced to flee his homeland in search of safety and opportunity. And at age 31, he found himself detained at the Otero County Processing Center in Chaparral, New Mexico.

Like many Venezuelans, Yofer participated in protests against the government—activism that came with a steep price. He said the CICPC (Venezuela's national police) repeatedly detained and beat him—he ultimately had no safe choice but to flee the country.

"Solitary is horrible...the guards damage us psychologically."

Yofer experienced the psychological torture of solitary confinement while detained at Otero. "Solitary is horrible," he told us. Guards allowed him just ten minutes daily for family calls and routinely accused all Venezuelan detainees of gang affiliation with Tren de Aragua without evidence.

Yofer spent 17 days in solitary in a tiny cell with severely restricted yard access. Initially, guards told him and others that ICE had ordered their isolation, but Yofer later learned the decision had been made by MTC, the private company that operates the facility. Even outside of solitary, he continued to face arbitrary cruelty in the detention system. Even though he had been ordered deported four months earlier, Yofer remained in Otero, taking medication for anxiety, depression, and nightmares brought on by his prolonged confinement.

"The guards want to damage us psychologically," Yofer explained, describing how some guards treat detainees with explicit racism. The experience has changed him. He now avoids speaking to guards for fear of being returned to solitary confinement.

Yet even in these dehumanizing conditions, Yofer believes strongly in second chances and human dignity. "If I were in the guards' position, I would never put people in solitary. I would talk to them instead and explain the situation calmly," he told us.

"We are not bad people. We are fathers and mothers who want to work."

He speaks with pride about how detainees in his and other units formed a brotherhood, sharing what little they have and supporting each other through the hardest times. For Yofer, maintaining this sense of community is an act of resistance. When the facility cut free phone privileges and instituted charges of 45 cents per minute—a cost many detainees had no way to pay—Yofer and others organized hunger strikes. Though these actions often resulted in more punishment, they maintained their solidarity.

Yofer's dreams for life beyond detention are both modest and profound: to be able to speak with his family and prepare traditional Venezuelan dishes like arepas con jamón and pabellón with passion fruit juice.

His message to ICE, MTC, and Otero officials is simple: "Give us a chance; trust us; we are not bad people. We are fathers and mothers who want to work." As he puts it in Spanish, "Con una oportunidad basta y sobra para hacerlo realidad"—one opportunity is enough to make it a reality.

Yofer's story, like countless others, underscores why New Mexico must pass House Bill 9, the Immigrant Safety Act. Our state cannot continue to be complicit in a system that strips immigrants of their dignity, subjects them to arbitrary punishment, and denies them basic human rights.