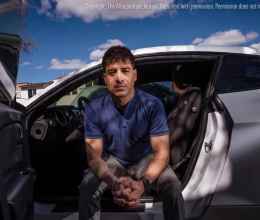

On July 22, 2019, Elaine Maestas’ life changed forever. Shortly after midnight, Bernalillo County Sheriff’s deputies fired 21 fatal shots at her sister, Elisha. Elaine’s family had called 911 seeking help for Elisha, who, in the midst of a mental health crisis, had entered her uncle’s home in Albuquerque’s South Valley where she was staying in her RV and hit him without provocation. The deputies who arrived on the scene did not help Elisha as her family had hoped. Instead, they escalated the situation by banging on the door, shining their flashlights through her windows, yelling commands, and brandishing weapons outside her RV. When Elisha, who had been experiencing hallucinations and was likely terrified, ran out of her RV, the deputies opened fire on and killed her.

Ever since that day, Elaine has been fighting to prevent other New Mexicans from experiencing the tragedy and loss her and her family have suffered. Most recently, that fight propelled Elaine to join the ACLU of New Mexico as Police Accountability Strategist. We sat down with Elaine for a conversation on her journey from grieving sister to social justice advocate.

The Torch: What drove you to become an advocate for police accountability and reform?

Elaine Maestas: Before my sister was killed, I never thought in a million years that this could happen to me or my family. It was something that I’d seen on the news and that I knew happened, but you never ever think it’s going to happen to you. And that was a huge wake-up call for me. If this happened to my sister and to us it can really happen to anybody. And it happens all the time. So, that’s how I started my journey — just asking questions like why and how did this happen? And what can I do?

TT: Can you tell us a little bit about your sister, Elisha?

EM: We lost our mother at an early age to a house fire. I was 14, Eisha was 11, and my brother was six. After, my father got really depressed and started drinking and he ended up getting cirrhosis of the liver. My sister was going to school to become a medical technician during that time but she put everything on hold when my dad got sick. And she really became his caregiver. She gave up a lot of her young adulthood to take care of my father and put a lot of her own personal goals on hold. So my father passed away in 2013 and my sister ended up getting a job as a phlebotomist and was working as a caregiver for my uncle. And that’s just how Elisha was. Someone who was very much a caregiver. She was just a very giving, selfless, loving person.

"So, that’s how I started my journey — just asking questions like why and how did this happen? And what can I do?"

TT: When did Elisha start to experience mental health issues?

EM: In December of 2017 she was involved in a car accident and she got a CAT scan done because she hit her head on the windshield. It showed she had a growth in her skull plate. After discovering that, she went to see a neurosurgeon and found out that the growth was creating intracranial pressure and that began to get worse. So from December 2017 to June 2018 she was in and out of the doctor. In June of 2018, she had surgery to remove it. But in the weeks following, her symptoms began to increase. She started getting stroke-like symptoms where her face would droop, her speech would slur, she couldn’t open a door sometimes and she would get frustrated. Elisha’s mental health issues started to peak in 2018 in the middle of the year and from there it was a rapid decline. Elisha was really afraid. She started hallucinating.

TT: You and your family had called the police for help for Elisha before July 22 so officers were aware that Elisha had these struggles. But instead of helping her, they escalated the situation. Can you say a little bit about that?

EM: Yes. There’s one deputy in particular that made things worse and I truly believe that if he was not there that night my sister might still be here. He told Elisha to “act like an adult” at one point. He went to his car at another point and got a bean bag shotgun and popped it at the door and was banging on the door. I am blown away by the level of unprofessionalism and brutality they displayed and the complete disregard for my sister’s life.

TT: In the aftermath of the tragedy that you and your family experienced, what did you start doing to enact change?

EM: At first I was very much overtaken by grief so I started interviewing at every chance that I had to make it known that this was wrong and that the sheriff’s deputies made it happen. That police needed to wear lapel cameras. We didn’t have a completely clear understanding of what happened to my sister because BCSO deputies, at the time, did not wear body cameras. And in fact, Sheriff Manny Gonzales steadfastly refused to adopt them for his department.

While I was in the process of doing that I met a reporter that told me that I should go to the ACLU and to ask for Peter Simonson. About a week and a half after I went to the ACLU and I met with Peter and I just cried and let my heart out telling him everything that my family just went through.

"The work isn’t done because there’s still so much wrong with policing in our state. More change is needed."

TT: What came next?

EM: After that meeting with Peter, I partnered with the ACLU and other community members and my family and we just started going to the commissioner meetings and letting them know that we needed lapel cameras and crisis intervention training. Three months after my sister passed away and after us consistently going to commissioner meetings, the county commissioners came up with a resolution allocating starter funds for lapel cameras, but Manny Gonzales refused to adopt them. I knew at that moment that I needed to start fighting on a state-wide level, so I started emailing every legislator that I could, the governor, and anybody that I thought would listen to me. I protested outside the Capitol during the special legislative session they held in the summer of 2020 and I protested a lot of other times too.

I was really just trying to raise awareness that we need body cameras on every single deputy and officer in our state. About a year later, a bill mandating body cameras on all police in the state was passed. So that was a huge victory for us, but the work isn’t done because there’s still so much wrong with policing in our state. More change is needed.

TT: What does the position of police accountability strategist mean to you?

EM: This position is honestly the best thing that has happened to me since my sister passed away. It gives me a chance to make the change that I’ve been fighting for in our community. I’m not just advocating for the kind of policing my sister deserved that night she was killed. I’m advocating for the change that each New Mexican deserves today. It has been proven for years and years now that we can’t leave it up to leadership to hold officers accountable for brutality and misconduct. We just can’t. We need to pass statewide laws that hold officers accountable and prevent brutality from happening to begin with.