When Duke Rodriguez, CEO of the cannabis company Ultra Health, was exploring where to open a new production facility, there was one key factor in mind: it had to be north of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection interior checkpoints.

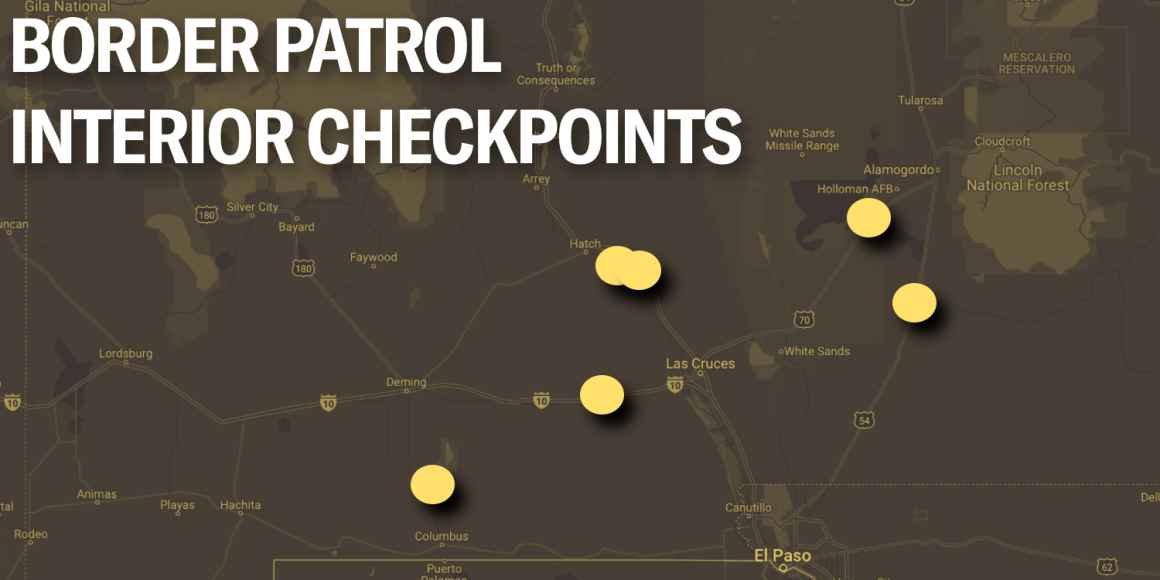

That’s because the checkpoints, which Customs and Border Protection can operate up to 100 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border, have become a troubling barrier to New Mexico’s legal cannabis industry, threatening the state’s legalization equity goals and potentially limiting the ability of residents near the border to tap into the lucrative, growing industry.

“We purposefully bought land in Tularosa,” Ultra Health CEO Duke Rodriguez said, “because it is beyond the reach of the checkpoints.”

Medical marijuana has been legal in New Mexico since 2007 and in 2021 the state legislature voted to allow adult-use recreational cannabis. The legalization bill included several measures aimed at helping communities of color and those most affected by the country’s war on drugs to benefit from the new industry.

Cannabis, however, remains illegal at the federal level, so companies operating legally within New Mexico can be stopped while transporting their product or the revenue from their business through federally-run checkpoints. That is concerning to Barron Jones, senior policy strategist at the ACLU of New Mexico.

“The checkpoints could have a disastrous impact on the state’s equity goals rolling out legal marijuana,” Jones said. “Folks within 100 miles of the border, they won’t have the same opportunities to participate in the industry as folks living on the other side of the 100-mile border.”

Ultra Health operates statewide, including several retail locations within 100 miles of the border. But the threat of federal enforcement means they likely will keep their production and manufacturing facilities – and the jobs they bring with them – north of the checkpoints.

“We have faced our employees being detained, we have faced having cash and cannabis confiscated and not returned to us,” Rodriguez said, adding they’ve dealt with about half a dozen seizures at CBP checkpoints. “We’ve had our employees fearful of being arrested, being detained, they’ve been fingerprinted.”

“The checkpoints could have a disastrous impact on the state’s equity goals rolling out legal marijuana”

Although none of his employees have been prosecuted in relation to those seizures, Rodriguez said they are deeply traumatic experiences – he’s received calls from employees in tears, worried about facing criminal charges for participating in what in New Mexico is a legal industry.

“The first time it happened to us we thought it was an isolated incident,” he said. “Now I’m pretty convinced that (the agents) enjoy the thrill.”

Emily Kaltenbach, New Mexico state director for the Drug Policy Alliance, said checkpoints have been an issue since the early days of medical marijuana legalization in the state.

“There are so many patients I’ve talked to who are afraid to travel with their medicine,” she said. “Many of them have been stopped and harassed and had their cannabis taken, their medicine taken, from them.”

It’s a challenge most other states that have legalized cannabis do not have to deal with. Kaltenbach, who is also the chair of the state’s Cannabis Regulatory Advisory Committee, said colleagues working on legalization outside of New Mexico are sometimes shocked to hear there are federal checkpoints north of the border.

Because the checkpoints only stop northbound traffic, someone growing marijuana in Albuquerque could easily transport it to Las Cruces. But someone growing the plant in Las Cruces and trying to sell in the northern part of the state would risk seizure at a checkpoint like the one on I-25, south of Hatch, or the two south of Alamogordo.

That’s a particularly concerning challenge for small and micro cannabis businesses who can’t afford to have their product or income seized, Kaltenbach said. Those businesses are central to the equity goals inscribed in New Mexico’s law legalizing adult-use cannabis.

“(The presence of internal checkpoints) has a chilling effect on their business,” she said. “The idea that they can’t transport north out of the southern part of the state is concerning, it limits their market.”

Rodriguez, with Ultra Health, has met with active and potential growers in Las Cruces and in Berino, near El Paso. He’s worried about how prepared those smaller businesses are for the checkpoints.

“The first thing I say is, ‘How do you plan on moving (your product)?’ and they say, ‘What do you mean?” Rodriguez said, adding that transporting cannabis at a commercial scale is not particularly subtle, requiring U-Haul-size trucks. “They will be in every case asked, ‘is that marijuana that I smell?’ … and it’s going to be seized.”

New Mexico Cannabis Control Division Spokesperson Heather Brewer said in an email that the agency has heard concerns about the impact of the checkpoints from active and potential growers in the southern part of the state. The agency, however, has not received any guidance from federal agencies on how they plan to enforce federal cannabis laws in the state.

“However, we know that cannabis is still illegal federally and that federal agents are empowered to enforce federal laws,” Brewer said. The agency, she added, “is committed to advancing social equity in the industry throughout the state.”

The impact of the checkpoints on the cannabis industry are already being felt. Las Cruces Councilmember Gabe Vasquez said it hurt to see Ultra Health invest in a new facility in Tularosa, after his city “strongly supported the legalization of cannabis,” he said.

A sizeable amount – 40 percent or more, according to one Ultra Health-sponsored study – of cannabis revenue is expected to come from tourists, primarily from Texas, shopping in cities such as Las Cruces. But it’s possible production and manufacturing companies will follow Ultra Health’s lead and set up north of the checkpoints.

“It’s definitely going to impact us here in Las Cruces as far as our ability to participate in this economy and it’s a shame,” he said. “In many ways, it’s definitely unfair.”

Rodriguez, Kaltenbach, and Vasquez said they see racist undertones involved with the presence of checkpoints in the state, which has the highest Latino share of the population in the U.S. Many of the communities that will face the additional challenges checkpoints pose are majority Latino and have struggled with a lack of quality jobs.

“It’s definitely going to impact us here in Las Cruces as far as our ability to participate in this economy and it’s a shame”

“Latinos also face a higher degree of questioning and scrutiny and targeting at checkpoints,” Vasquez said. “That has been going on for many years.”

Rodriguez, who for a time lived in El Paso and who frequently drives around the state, said he’s seen first hand how people of color are treated, as well as the fact the checkpoints primarily affect residents in majority Latino communities.

“We don’t see (people) getting stopped as they’re coming across Amarillo … into Hobbs,” he said. “But you can expect those brown people to be questioned as they’re coming outside of Las Cruces or Lordsburg.”

For Vasquez, the checkpoints are a clear sign of the need for change at the national level, an idea echoed by Rodriguez and Kaltenbach.

“I think the federal law needs to catch up with the states that are rapidly legalizing adult-use recreational cannabis and let people build an economy that lets people make a living,” he said. “It’s incumbent on Congress to once and for all legalize adult-use cannabis.”

Jones, at the ACLU of New Mexico, pointed out the checkpoints themselves are a problem. He suggested it’d be better if they shut down.

“They interfere with people’s reproductive care, medical care, the checkpoints pose all sorts of problems for people in the southern part of the state,” he said. “Fear-based politics allow those checkpoints to thrive.”

Contact Invesitgative Reporter Leonardo Castañeda at [email protected]