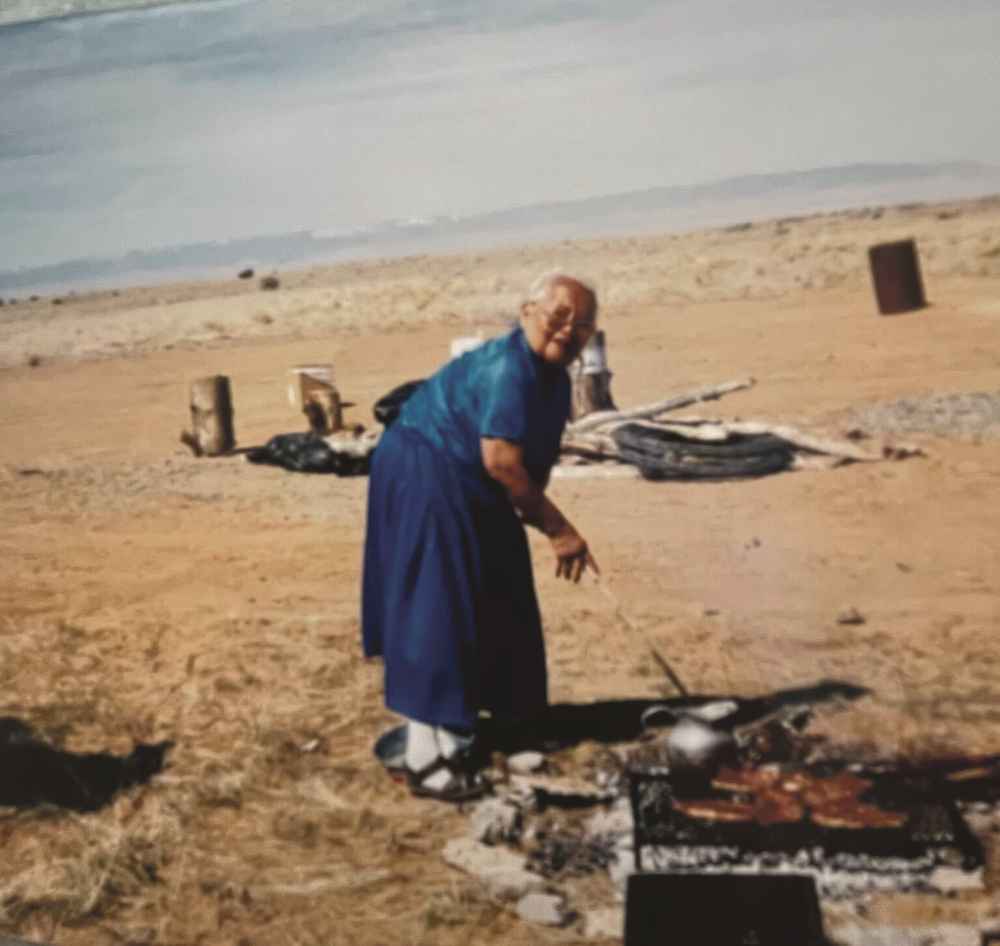

My mom was born in 1958 and given up for adoption by her biological mother. Her maternal aunt, known to my brother and me as “Grandma Louise,” who only spoke Navajo, stepped in to be her mom. Grandma Louise loved my mom and raised her under Navajo traditions in Farmington, New Mexico. My mom learned from a young age to speak fluent Navajo, make traditional foods, and weave customary skirts. In fact, she later became Shiprock’s Miss Northern Navajo in 1980. How her story would have differed if she had been adopted and raised outside of Navajo culture and community remains an issue to ponder; similarly, how my story would have differed.

Even as the 1970s ushered in the self-determination era, giving Tribes autonomy to administer education and health services, the wounds incised by U.S. history formed deep, tender scars that show today.Every Native family has a story about children who were adopted or placed in foster care. Some children were fortunate to be raised by an extended family and community. Those not so fortunate, however, were likely stripped of their cultural identity—often forcefully. Elders remind us that it only takes two generations of kin disconnected from their language and culture to kill the language and culture.

Tribal Sovereignty

The annihilation of Indigenous identity is deeply rooted in U.S. history. The boarding school era began over 150 years ago, forcibly placing Native children in schools hundreds of miles away from home to “kill the Indian in him, save the man.” Grandma Louise – just a child at the time, told stories of having to hide when federal agents arrived.The 1950s began the termination era, where removal, relocation and family-separation policies were intended to kill Indigenous culture, dismantle tribal sovereignty, and terminate the U.S. government’s trust responsibilities owed to Tribes.

Cultural resilience prevailed, but the wounds were permanent. Even as the 1970s ushered in the self-determination era, giving Tribes autonomy to administer education and health services, the wounds incised by U.S. history formed deep, tender scars that show today.

ICWA

In 1978, Congress enacted the federal Indian Child Welfare Act in response to the unnecessary removal of Native children from their families and tribal communities. ICWA intends to protect the best interests of Native children by ensuring state foster care and adoption proceedings prioritize their placement with extended family and community. Research shows that Native children in the child welfare system do better emotionally, academically, and socially when this outcome is achieved.

However, in 2018, a federal district court in Texas, in a widely criticized decision, held that ICWA violates the U.S. Constitution. That decision was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The American Civil Liberties Union, along with its 13 affiliates (including New Mexico), submitted an amicus brief in support of preserving Native American families, respecting the cultural heritage of Tribes, and advocating for children’s rights and a child’s interest in family integrity

Thankfully, in a huge victory for tribal sovereignty this June, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the attack against ICWA in Brackeen v. Haaland. This landmark ruling reaffirms legal precedent upholding tribal sovereignty, hard-fought rights over tribal land and water, health care, criminal and civil jurisdiction, and tribal self-governance—a win for New Mexico’s 23 federally recognized Tribes, Nations, and Pueblos.

Most importantly, it ensures ICWA’s provisions will continue to protect Native families and keep them together.

Photo above right: Rolinda ("Ro") Sanchez. Photo above left: Grandma Louise.