Originally published in the Summer 2017 issue of the Torch

Year after year the cycle of violence continues.

According to the New Mexico Interpersonal Violence Data Central Repository, a staggering 17,757 domestic violence cases were reported to law enforcement in 2015, and a report from the same year by the Violence Policy Center found that our state had the third highest rate of female homicides by male offenders in the nation. These sobering statistics do not even capture the countless additional incidents that go unreported each year. We must put an end to the domestic violence crises that deprives victims of their fundamental ability to live with dignity, but the solutions currently in place are not working.

The United States is addicted to punishment. Despite lip service to concepts like ‘rehabilitation’ and ‘correction,’ when you scratch the surface our criminal justice system is really just a machine for the administration of punishment. Insert a crime, the machine spits out a prison sentence. We’ve fallen prey to the insidious idea that if we can only punish harshly enough, people will stop hurting others. But if our criminal justice system only punishes the symptoms without ever tackling root causes of the problem, our communities will never be any safer.

The ACLU of New Mexico believes that our communities will be safer in the long run if we stop using outdated and ineffective tactics like mass incarceration, and move towards a more holistic, evidence based, and community-centered approach to fighting crime. That’s why we are working with a new coalition we helped launch last year called New Mexico SAFE, which is dedicated to reforming our criminal justice system so that it addresses the root causes of crime and violence. An important part of that work is partnering with formerly incarcerated people and survivors of violence to learn more about how we can provide lasting justice to those who are hurt by crime, as well as get offenders the treatment and rehabilitative services they need to break out of their destructive behavioral patterns.

We sat down with Tanya Romero who is Residential Shelter Services Director at Esperanza Shelter for Battered Families, to hear about her first-hand experiences with domestic violence as well as her thoughts on how we can make lasting transformative change.

Can you tell me about your personal experience with domestic violence?

The abuse started roughly about eight years ago. I’ve been married twice in my life. My second husband was my offender. After my first marriage of fifteen years ended, I reconnected with my eventual offender who I knew from high school. We reconnected on social media and at that point I was still vulnerable and new to being out of my marriage.

I started to see signs like him asking, “Why are you wearing that?” “Why are you trying to bring attention to yourself?” “How come you visit your family so often? “ “Don’t you love me?” And I took him as, “My gosh. This guy is really into me. He’s really protective of me.” And I’d never had that type of affection to that extreme. Then about four months into the relationship he said either I marry him or he would leave me. And at this point I had totally fallen for him so I said, “ok I’ll go ahead and marry you.” That’s when the violence started to escalate. The physical violence started. The threats started. My children were impacted by that as well, as far as being emotionally, verbally - and in the case of my youngest child - physically abused.

Knowing that I wasn’t ready to leave the relationship, I stayed with my offender and I put my daughters in care of my mother and my son with his father. It was probably the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do, but I knew they weren’t safe. I continued to stay in the relationship for another three and a half years. He had me right where he wanted. No kids, no friends. My job was suffering. I got a restraining order and then I would break that restraining order.

Then one day he physically assaulted me with a weapon. I managed to escape, go to a public location and call the police. It was the first time I’d ever called the police to report the violence. They asked, “Do you have a safe place to go?” and I didn’t. By this time I’d burned bridges with family and friends so the police said, “well how about Esperanza shelter?”

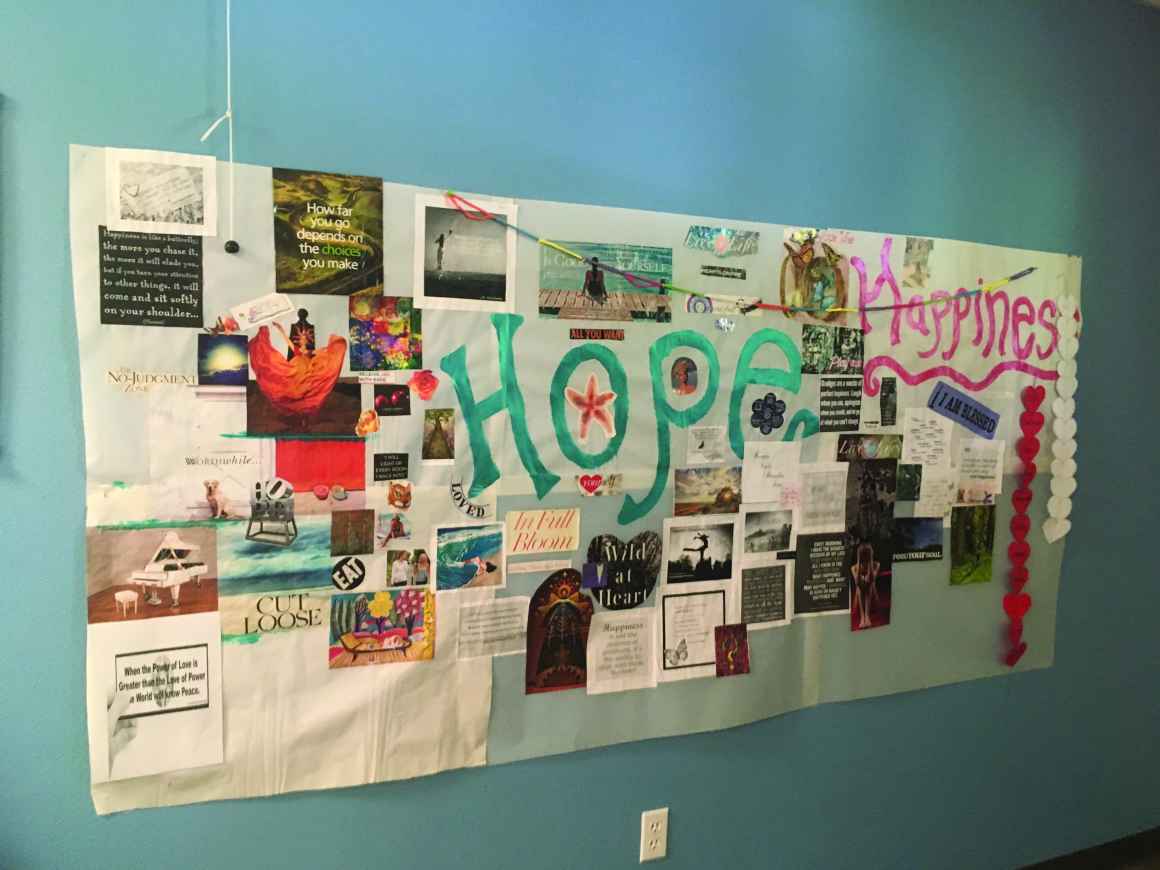

So I stayed in the shelter and it was really tough. I was scared, but I knew I had to be there to be safe. Esperanza is where I found my sisterhood among other survivors.

My offender is no longer here due to an overdose. He was an addict. There were also behavioral and mental health issues at play. They added fuel to the fire.

Is it how I wanted it to end? Absolutely not. I wanted him to get the help that he needed.

How did you end up working as an advocate for domestic violence survivors?

I worked on myself for two years after my offender passed away. After that, I got started volunteering at a crisis treatment center taking calls from sexual assault and domestic violence victims, and then I began my career in Rio Rancho working at a shelter. Now I’m here at Esperanza. It’s been about a total of almost eight years.

What are the stigmas around domestic violence?

There’s always the stigma that it’s your fault. Why didn’t you leave? Why did you stay? That’s probably the most common, and it’s so unfair. People have no idea what it takes for someone to share their story. Education is key. I teach in schools, and its powerful how education can prepare others to be safe and raise awareness about what domestic violence is. It needs to start at a young age because that’s where kids often learn the pattern because they see a parent being violent.

What do you think some of the leading causes of domestic violence are?

Lack of resources and lack of jobs are some of the causes I see. It’s also generational, it’s historical violence and it has to start somewhere. I have compassion for that, and many people don’t understand why I would have compassion for that after what I’ve been through. I’ve taken a lot of initiative to educate myself. Domestic violence is a learned pattern, a learned behavior. These individuals are not born as evil or as monsters, it’s because they themselves have been hurt. How do we start to fix the cycle of violence?

You have an offenders program aimed helping those who have abused others to change their lives. Why is it important to offer that program rather enhancing the punitive measures already in place?

I feel putting more punitive measures in place would do more harm than good. These are quick solutions that don’t really focus on the individuals who need the help. After long-term incarceration, offenders come out even more violent. There’s no follow up within the legal system as to what programs are they going to for rehabilitation and recovery. Where are the programs after incarceration for offenders? We release them back to society without the tools that they need.

What are the barriers that undocumented immigrants are facing with domestic violence?

It’s the fear of being taken. It’s the fear of families being broken apart. We are a sanctuary city in Santa Fe so it feels safer for many to reach out here. But immigrants are still afraid. When you’re undocumented, that’s part of the cycle of abuse because offenders use their victims’ immigration status against them or threaten to report them or take away the kids. With our current administration it’s really scary.

How can we break the cycle of violence?

When it comes to court hearings, it would be beneficial to make it a state law to mandate offenders to the batter intervention program (BIP) and there should be oversight to ensure that offenders are actually attending the program. We’re here to help break the cycle, and that involves offenders. It doesn’t exclude them. The BIP program that we have here has been going strong for a number of years and we’ve seen positive results from that. I’m very proud to work for an agency that supports that because not many agencies are like that in this field.

I also feel that it would help if there was more support from the state with addiction and mental health issues in the community. We need more laws that support both victims and offenders and my vision of that involves more resources and education in the community.