Etta Arviso didn’t have running water when she first moved to her home in Bloomfield in the early 1990s – it wasn’t even connected to the city’s water system.

So Arviso, a Navajo citizen and lifelong San Juan County resident, went to a meeting of the city’s water district, demanding her home be connected to the system.

“I was told, ‘Why don’t you just take your backhoe and dig water from the river to your house?’ and I got up and I raised my hand and I said to the committee ‘Don’t talk to me like that,’” Arviso said. “I said ‘How dare you, I like to flush my toilet like the rest of you.’”

Arviso eventually got her water connection via a direct water line. But in more than a half-dozen interviews around the large, mostly rural county, Navajo residents told the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of New Mexico that their needs and priorities continue to often be ignored, minimized, and misunderstood by local officials.

Among the most basic barriers, they said, is a lack of county representation. Indigenous residents, the vast majority of whom are Navajo, are about 40 percent of San Juan County’s population. That makes them the largest single racial or ethnic group in the county. The Indigenous share of the population is likely higher – the U.S. Census Bureau has admitted Indigenous residents were severely undercounted in the 2020 decennial census.

"Who are we going to vote for if we don’t have any person in there that is going to know our concerns?”

Despite that, San Juan County commissioners approved a new redistricting plan that packs Indigenous voters into just one of the five commission districts, diluting their voting power. A map proposed by the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission (NNHRC) would’ve given Indigenous voters a majority in two districts.

“The current redistricting map adopted by San Juan County repeats the long and shameful history of disenfranchising Indigenous communities,” ACLU of New Mexico’s Indigenous Justice Attorney Preston Sanchez said. “The county is obligated under law to ensure that the redistricting process results in Indigenous voters having adequate legislative representation by candidates of their choice.”

In February, the ACLU of New Mexico alongside the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, the UCLA Voting Rights Project, the Navajo Nation Department of Justice, and DLA Piper sued on behalf of the NNHRC and five Navajo voters. The lawsuit seeks the implementation of a new map where Indigenous voters are able to elect representatives of their choice in two districts.

Debra Yazzie, vice president of the Navajo Nation’s Shiprock chapter, said she was upset when she saw how the map was drawn by the commission.

“It is imperative that we have representation from our communities,” she said, adding that those elected leaders can be “representing us and advocating for us at the county, state and federal levels.”

‘If you need help … there’s nothing’

Nestled in the Four Corners region of northwestern New Mexico, San Juan County’s cultural and natural richness is perhaps only matched by its geological wealth. The county is home to vast oil and gas reserves, as well as coal and uranium.

It’s also covered in large part by the Navajo Nation, which extends into parts of Arizona and Utah and covers part of the Navajo people’s traditional homeland.

But for many Navajo residents living in rural and semi-rural communities disconnected from running water and electricity, living on unpaved roads far from emergency services, the region’s beauty belies its harshness.

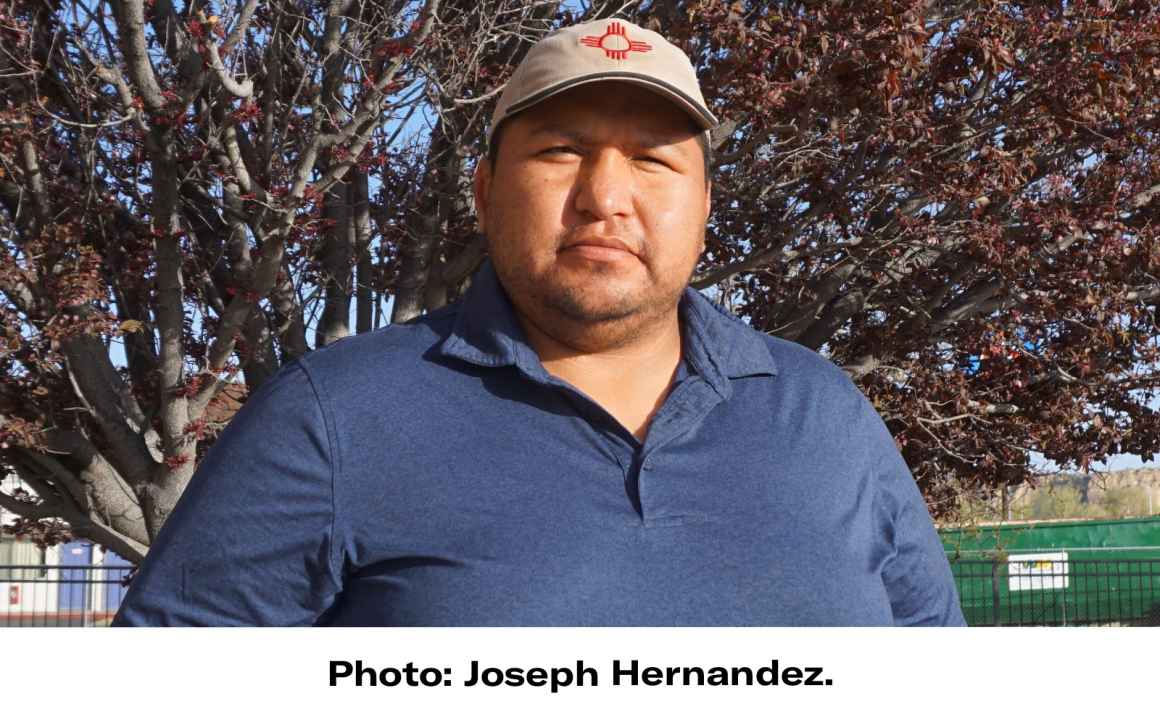

“There’s a lot of unmet needs that we have in our communities,” said Joseph Hernandez, 34, a Navajo resident of the small community of Beclabito near the Arizona border. “There’s a whole bunch of layers to it that you really have to live there to truly understand it.”

He said San Juan County could help provide basic infrastructure needs like paved roads and bridges that would better connect rural residents with larger towns and necessary services. They could also provide rural addresses to homes, which would help with mail service and emergency response.

“You expect to make a phone call and 911 will answer,’ he said.

But for many Indigenous residents in San Juan County, that’s not the case.

“Even if the fire department and the ambulance come, they can’t find you because they’re trying to locate your house because there’s no rural addressing.”

“There’s a lot of unmet needs that we have in our communities. There’s a whole bunch of layers to it that you really have to live there to truly understand it."

Those concerns were echoed by Ramona Begay, who lives in White Rock, a rural community near Chaco Culture National Historical Park. She used to work for the park, she said, but her commute involved crossing multiple washes that would be impassable during the rainy season. She had to pack four days’ worth of clothes every time she went to work, in case she’d be unable to return.

“If you need any help of some sort, there’s nothing,” she said.

The unpaved roads are in such bad condition, she has to go to Farmington twice a year to get new tires for her truck, as well as replacement parts for the wear and tear. That’s where she also has to go to get her groceries, as well as gas for her hours-long commute, something she said is common among rural Navajo residents.

“We’re just boosting the economy of San Juan County and that’s all we’re good for,” she said. “But none of those revenues come back to us.”

Yazzie, in Shiprock, spent her childhood playing basketball in the Four Corners. She won a state basketball championship with Arizona’s Window Rock High School and spent the summers playing against members of the state championship-winning Shiprock High School girls’ basketball team.

Now 51, she still coaches youth basketball sometimes, among other sports, but as a first-time chapter official, she’s focused on issues like a lack of waste transfer stations and dangerous speeding on US-64. The road connects Bloomfield and Farmington through Shiprock and into Arizona and is a frequent site of car and semi-truck crashes, she said. It’s also the road many school buses take to and from picking up Navajo children.

The community has been pushing for additional signs and traffic enforcement to slow down vehicles, Yazzie said, with mixed results.

‘If we had people that ran from our community and were elected,” she said, “then a lot of these issues would be addressed.”

‘It comes down to priorities’

All residents who spoke with the ACLU of New Mexico said many of their basic issues are complicated by San Juan County’s checkerboard jurisdiction.

Parcels of land belonging to private owners, the county, state agencies, the federal government and the Navajo Nation are jumbled and interspersed throughout the region. That can make it hard at times to know which government is supposed to provide which services in any given location.

But they also highlighted how county officials could often do more to take ownership of county responsibilities, as well as be a stronger advocate for ensuring services are provided to all county residents, regardless of jurisdiction.

"If we had people that ran from our community and were elected then a lot of these issues would be addressed.”

“I think it comes down to priorities,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez first became aware of a lack of representation when he went before the district’s school board to advocate for his middle school as a member of the student council. There was only one Indigenous person on the school board, he said.

“There’s a limitation on representation and it’s a reality here,” he said.

That lack of representation is reflected in a lack of Navajo-speaking elected officials, he said. That can hinder communication with voters because many community members prefer the language and feel less comfortable voicing their concerns in English.

“If you don’t speak the language, you’re not getting the whole picture,” he said.

Indigenous voters often don’t even get the kinds of outreach and visits from candidates during election seasons, let alone in regular years, that other parts of the county get. That’s according to Elvira Dennison, who lives in the small community of Naschitti, roughly halfway between Shiprock and Gallup.

Speaking at the Naschitti chapter house while the outside wind swirled, threatening a haboob, Dennison talked about how her community often gets overlooked by county officials who don’t even know where it is – some have incorrectly told her they can’t help her because she’s in neighboring McKinley County.

“We’re always left out our community,” she said.

“There’s a limitation on representation and it’s a reality here."

Dennison lived in Albuquerque for a while and since coming back, she said she spent time serving as a poll worker as well as at the community’s laundromat where she’d try to educate residents about upcoming elections. People struggle to choose between candidates they’ve never met and often have never even heard about.

“We’re voting for people who we don’t even know,” she said. “We don’t know their background, we don’t know if they’re willing to work with the community.”

Dennison said candidates from bigger cities or outside the Navajo community struggle to understand life in the small enclaves that dot San Juan County’s vast rural landscape. They almost never even campaign in places like Naschitti or do outreach to understand the needs.

“San Juan County elections, we’re not being heard, we’re not being involved, we’re not being counted,” she said. “We’re being left out, we’re just pushed aside.”

That was echoed by Yazzie, in Shiprock, who added that non-Indigenous officials are often unaware of or forget vital historical context such as the treaties between the Navajo Nation and the U.S. government.

Instead, she said, Navajo residents end up shut out of elected office. She said efforts to dilute their vote is intended to hurt Navajos’ electoral power.

Yazzie, like all the residents interviewed by the ACLU of New Mexico, is not a party to the redistricting lawsuit but said she hopes for commission lines that allow for districts representative of the community. The alternative is disenfranchisement.

“That redistricting does hurt us,” she said, “because who are we going to vote for if we don’t have any person in there that is going to know our concerns?”